Machine counting of STV elections: faster and fairer

As we face the prospect of a fourth day counting votes in the 2016 General Election, it is time for Ireland to consider following Scotland’s lead and implement machine counting of single transferrable vote (STV) elections. First and foremost, I am not talking about revisiting the failed electronic voting experiment. I am quite sceptical about such systems, as they rely on the integrity of the technology with respect to not only the count, but the very process of voting itself. What I am talking about is the counting process. Machine counting of STV elections has taken place twice in Scotland, most recently using systems supplied by a Derry-based company. The process is significantly faster, with counts taking a few hours rather than a few days. It is also, perhaps crucially, significantly fairer.

How does it work in Scotland?

Votes are cast in exactly the same way as in Ireland at present. You simply mark your ballot paper and place it in a ballot box in the same manner you always would records are kept at the polling station of how many people have voted, and should correspond to the number of ballot papers in the box once it is sealed. So from the outset, there is a paper-based poll that can always be hand counted in the event of any systematic failure.

The poll is verified by hand

Once the count commences, the ballot boxes are opened out onto tables and the poll is verified (checked to ensure that the number of ballot papers in each box corresponds with the number recorded by the polling station) by hand. This process involves counting the ballot papers into bundles of 100.

It is after this process that the machines kick in. The bundles of 100 are placed on top of a scanner and fed in one at a time. A computer then uses optical character recognition software to read the preferences indicated on each ballot. The counting agent operating the computer has to manually verify that the computer has correctly identified all of the preferences indicated on the ballot, and correct any obvious errors in the recognition. Any ballots that are in any way questionable or potentially invalid are referred for adjudication, just as would happen in a hand count. The process typically takes around 3-4 seconds per ballot – so longer than a hand sort – but, crucially, you only have to do it once. The whole process can be overseen by the candidates and their teams. The computers have two screens – one facing the operator and one facing outwards. You can see each ballot as it is fed in and verify that what was on the paper is what’s on the screen. Candidates’ agents still tally votes just as they would a hand count.

Count staff feed ballots into the computer and verify the recognition of preferences. Candidates and agents can oversee the process on computer screens.

However, once all of the ballot papers have been fed in, checked, and disputed ballot papers adjudicated upon, the computer can then run through the whole election count instantly. In my home local authority, STV election counts take the same length of time it takes to conduct a simple first past the post count for the same electoral area, with the same size of count staff, in general elections (approx. 3-4 hours).

fair distribution of surpluses

Aside from the expediency of machine counting, the system is also much, much fairer. A difficult problem with STV is when an elected candidate has a surplus to redistribute, how do you decide which of their votes are the surplus ones to be redistributed? In Ireland, this is done at random. This is obviously grossly unfair.

Consider the example of Dublin South-West. John Lahart was elected at the 11th count with a surplus of 190 votes out of 11,402. If a newspaper were to print a poll with a sample size of 190 it would rightly be ridiculed for being so small as to be in no way an accurate reflection of the sentiments of the electorate. If such a small sample is unacceptable for hypothetical elections in opinion polls, it certainly unacceptable when real votes are concerned.

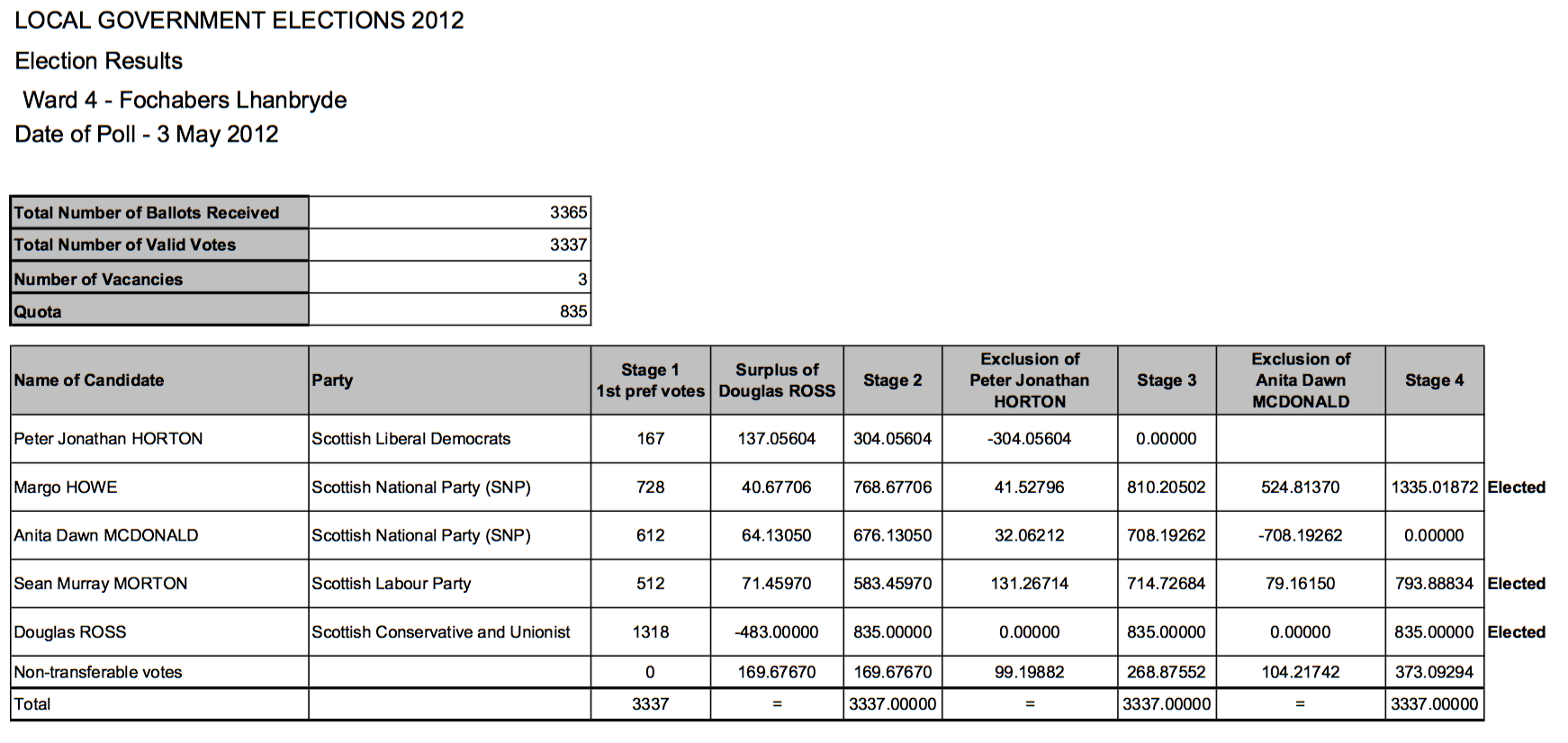

An example from a local election in Scotland, illustrating the fractional allocation of a candidate’s preferences.

The much fairer way is to count up ALL of the next preferences of that candidate, and then prorate them according to the size of the surplus. The result is fractions of votes that perfectly reflect the second preferences of the whole of that candidate’s vote. You can do this by hand, but in the above example it would mean counting over 11,000 votes just to allocate 190. It is hugely time consuming. A computer, however, can do it instantly.

So not only is machine counting quicker, it also makes it much easier to allocate surpluses more accurately.

Can it be trusted?

It has been put to me that such a system requires a lot of trust – in the software, the hardware, and the supplier – which is true. Just as the existing system requires a lot of trust in hundreds, if not thousands, of polling and counting agents. We have no reason to believe that counting agents would ever try to manipulate a count, nor should we have any doubt that the makers of the software or hardware would. There is always the possibility of error, which is evident from the recounts presently ongoing in the General Election. But while human error is random and unpredictable, making it much more difficult to spot, systematic error is, by contrast, comparatively easy to identify. Parties will still have been tallying votes at the verification, and overseeing the scanning process, so discrepancies in the system should be easy to spot. The actual code required to allocate votes once they have been fed into the system is incredibly simple, which a freshman computer science student should be able to write. It should be similarly simple to independently verify the veracity of such software.

Ireland is not exceptional. If machine counting of paper ballots works well elsewhere, there is no reason why it wouldn’t also work in Ireland. It is most certainly not prohibitively costly (in particular when you consider how much counting votes for four days must cost). Machine counting is many times faster than hand counting, and more accurate. Ireland should put the failed electronic voting experiment behind it, and follow Scotland’s example in implementing machine counting of STV elections.