What if the Scottish Parliament election is just a repeat of May 2015?

The 2015 general election produced a considerable spike in turnout in Scottish constituencies. Following the election, I produced a projection that adjusted the election result for the turnout spike, in order to provide a better picture of the political situation based upon “normal” turnouts. Unsurprisingly, on the basis of exit polling, the spike in turnout was overwhelmingly attributable to the SNP. Perhaps a little surprising was that the spike in turnout actually had relatively little effect on the results in most constituencies. Only Paisley and Renfrewshire South and East Renfrewshire would have been saved for Scottish Labour; Edinburgh West, Caithness, Sutherland, & Easter Ross, and Ross, Skye, & Lochaber being saved for the Liberal Democrats; and Berwickshire, Roxburgh & Selkirk gained by the Tories.

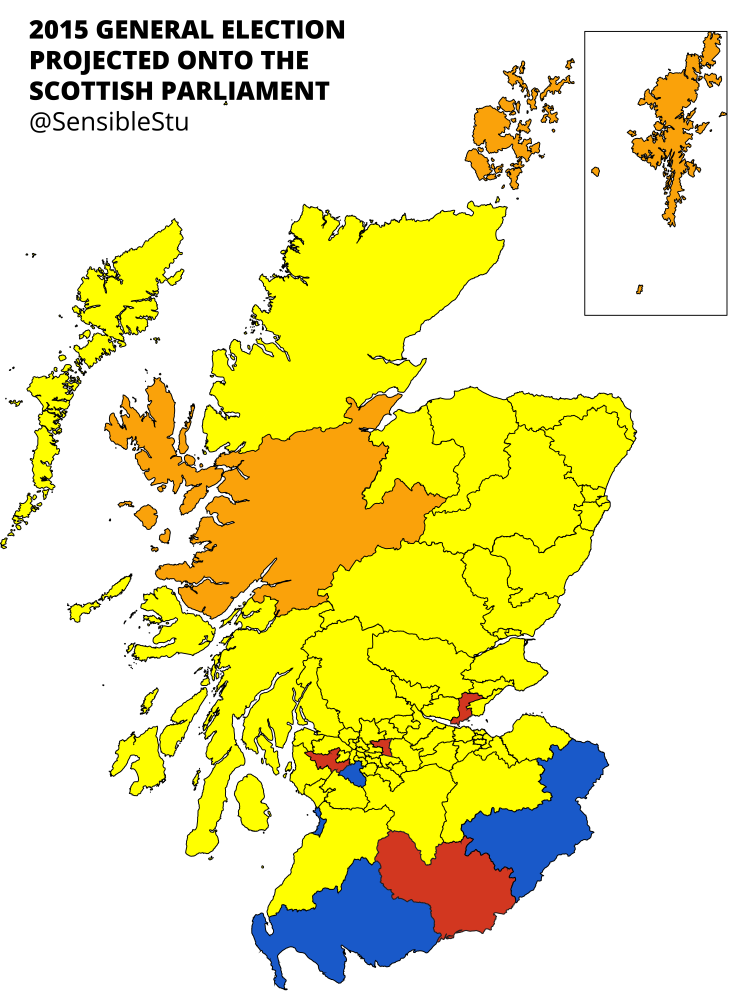

Just for fun (yes, this is what constitutes fun in my sad world) I’ve projected those results onto the Scottish Parliament, and below are the results. However, it’s worth noting how I arrived at this projection, beyond simply adjusting for turnout.

Other assumptions

Having adjusted the turnout to something approaching a “normal” General Election level (which, it is worth noting, is still higher than a typical Scottish Parliament turnout level), and applied it to the constituency section of my model, it then became necessary to apply these results to the regional list votes, which is obviously more difficult. As noted previously, parties typically suffer a degree of “regional leakage”, with constituency support going elsewhere in the regional lists. The leakage proportion from 2011 was used (which has Scottish Labour dropping off quite considerably, with the SNP remaining fairly solid). This produces a significant “other” vote. This “other” vote was then allocated to the smaller parties in proportion with the figures in the recent Survation polling.

It is worth reiterating that this is not a projection, it is an extrapolation. Its primary purpose is not to forecast May’s election, as we all know how Westminster and Holyrood elections can produce wildly different results even when they are relatively close to one another. Rather, this extrapolation provides a yardstick against which the coming election can be measured, as well as some indication of where parties ought to be focusing their efforts, in light of the fairly significant political reset that has taken place.

The result

The extrapolation sees another SNP near clean-sweep. Labour retains four constituencies: Coatbridge and Chryston; Cowdenbeath; Dumfriesshire; and Renfrewshire South. The Lib Dems retain their present two seats, and retake Ross, Skye, and Lochaber. The Tories retain their present three seats and gain Eastwood. In addition to those seats that change hands, the model produces a number of close contests: Edinburgh Central, Southern, Pentlands, and Western; Glasgow Provan; Dunfermline; Kirkcaldy; Aberdeen Central; Aberdeenshire West; East Lothian; and Dumbarton. If anyone is expecting some surprise results in May, they’ll likely come in one of those seats.

The extrapolation sees another SNP near clean-sweep. Labour retains four constituencies: Coatbridge and Chryston; Cowdenbeath; Dumfriesshire; and Renfrewshire South. The Lib Dems retain their present two seats, and retake Ross, Skye, and Lochaber. The Tories retain their present three seats and gain Eastwood. In addition to those seats that change hands, the model produces a number of close contests: Edinburgh Central, Southern, Pentlands, and Western; Glasgow Provan; Dunfermline; Kirkcaldy; Aberdeen Central; Aberdeenshire West; East Lothian; and Dumbarton. If anyone is expecting some surprise results in May, they’ll likely come in one of those seats.

Overall, the result is broadly in line with current projections. With a majority of 7, the SNP are down one seat on their 2011 result. Labour’s total of 29 seats is at the upper-end of expectations, with the Tories gaining three seats in the more traditionally Conservative regions of the North East, South, and Mid Scotland and Fife. Figures from the Lib Dems are distorted somewhat by the fact that 2010 saw incumbents in some seats faring relatively well against the SNP tide. Jo Swinson’s vote in East Dunbartonshire translates to a Lib Dem seat in the West of Scotland list, while Charles Kennedy’s vote in Ross, Skye, and Lochaber would probably be a gonner absent the man himself.

One striking feature of this extrapolation is how in line it is with current polling. While this might attest to the veracity of the polling, it may well also be that, as appeared to happen in polls in the run up to 2011, respondents are telling polling companies how they voted last time, as opposed to how they’re going to vote in May. In 2011, the polls only began to move to the SNP during the short campaign. It may well be that there’s still some movement to be seen in the polls after all.