Scottish Labour’s list selections: a democratic travesty

The Scottish Labour Party is currently in the process of selecting its regional list candidates for the forthcoming Scottish Parliament election. In previous elections the process has received little attention, owing to the expectation that Labour would win almost all of its seats in individual constituencies. However, with yet another rout predicted for Scottish Labour next year, the regional lists have become hugely competitive – with all bar-one of Labour’s incumbents seeking re-election aiming for a place on a regional list.

It has been apparent for some time that the regional list selections would be hugely competitive. Nevertheless, the process for selecting candidates appears to have been given little thought. For example, while a system of gender-based ‘zipping’ has been applied in order to ensure that candidates alternate by gender as they descend the list, no provision has been made for ensuring that women appear at the top of half of the lists. So if Labour wins five seats in Glasgow and West of Scotland (I am aware that this is ambitious), and three each in the others – and men top every list bar Lothians (which will be topped by Kez) – then the ratio of men to women would be 17/11.

However, even more worrying is the system used to rank candidates on the list – or the ostensible lack thereof.

The Party will use a simple single transferrable vote (STV) system to select candidates, the operation of which readers of this blog will doubtless be familiar. While this system is used around the world to elect representatives, including in local government elections here in Scotland, it is quite unsuitable for ranking candidates for party lists. The difference is that while in elections for councils the order in which members are elected doesn’t actually matter very much – when determining a ranking it is the order that is the whole point of the exercise.

The system that is to be used for selecting regional list candidates will require members to rank candidates, and any candidates meeting the quota will be added to the list. If more than one candidate is added to the list at that count then the candidate with the higher vote share will be placed higher on the list. However, with 12 candidates to be selected in most regions this could see candidates securing top spaces on some lists with as little as 8% of the vote. This means that candidates who have a small but solid support, and a large number of divided opponents could secure places near the top of the list even if the overwhelming majority of members find that candidate utterly objectionable. Preferences will be practically meaningless when it comes to selecting the top spots.

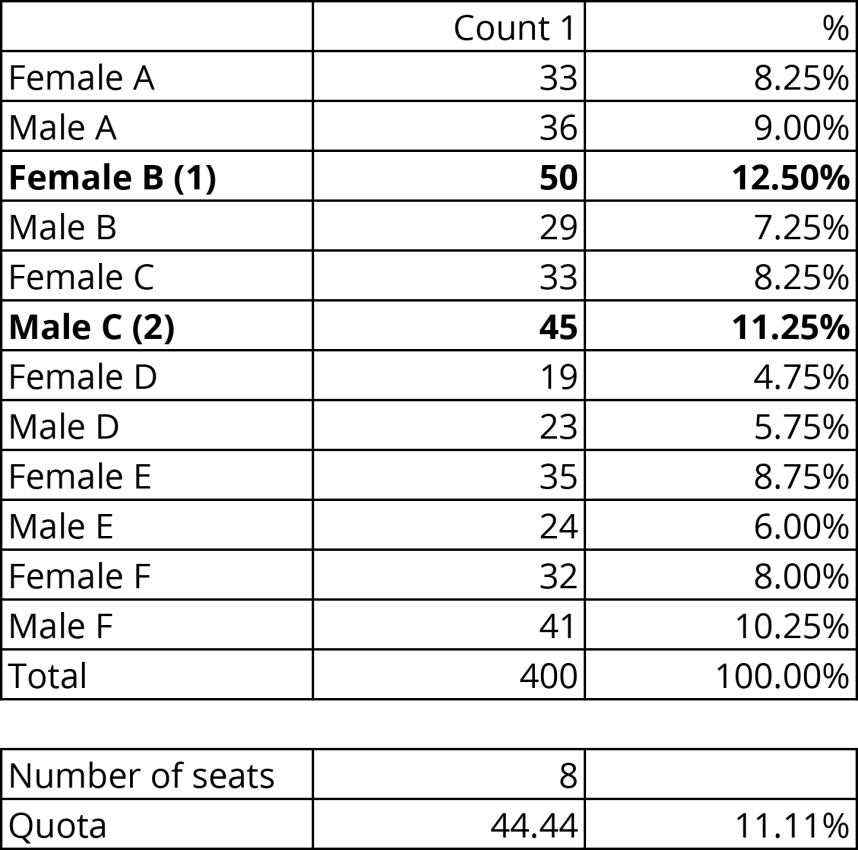

Consider the below example, where we’re selecting 8 candidates. Female B is has a small but solid support base of 12.5%. Most of the rest of the party absolutely despises her. Nonetheless, under Scottish Labour’s system Female B will secure the top spot on this regional list.

Single transferrable vote is supposed to be a preferential system – but allocating the top list spots in this way utterly fails to reflect those preferences.

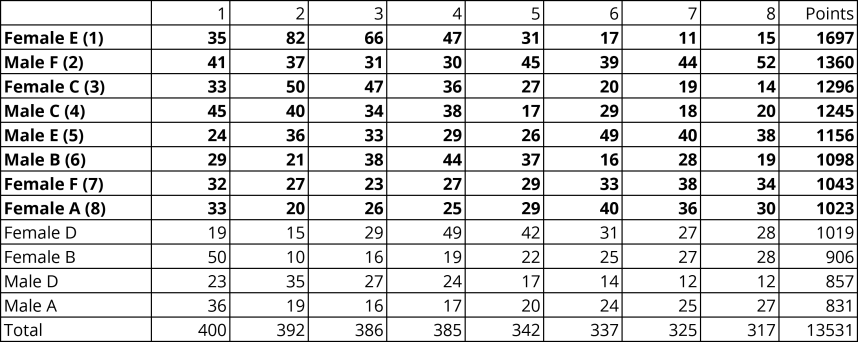

A better system might have been to use a Borda count method. Somewhat embarrassingly, readers will probably recognise this system as the one used to pick the winner of the Eurovision Song Contest. Under this method, members’ preferences correspond to points, with candidates ranked according to their points total. Expanding upon the above example, assume that first preferences are worth eight points, second preferences worth seven, and so on. In this example, the candidate winning the plurality of second and third preferences comes top of the list. In general, the candidates that rank highly are those with much broader appeal. Female B, by comparison, being detested by the overwhelming majority of the selectorate, doesn’t make it onto the list at all. Female B is Jedward – all-but guaranteed to get 12 points from the UK, but poorly regarded by the voters more broadly.

We’re all familiar with the drawbacks of the Eurovision method. Some decent tactics from groupings of candidates could well see them dominate the tops of the lists without resounding support, however the support necessary to do that under Borda is still far broader than that which would be required to do the same under the present rules.

So who does Scottish Labour’s current selection rules benefit? Because preferences won’t count for much near the top of the list, having a broad support base won’t matter. In general, people with a decent core of support without much local competition will do well. This probably benefits constituency incumbents over list incumbents – as they’re more likely to have a solid core of first preference votes from the seat they’ve represented for many years. It will also benefit constituency incumbents who have had few boundary changes over the years (like Elaine Smith) compared to those who’s seats have suffered substantial revisions (like Paul Martin). It benefits areas with a large contiguous political community over those that are more fractious – therefore favouring Fifers over those from the rest of the Mid-Scotland and Fife region. It benefits Rhoda Grant, and David Stewart – who faces strong but divided opposition from Sean Morton and John Erskine. And it favours men in the North East, with Jenny Marra and Lesley Brennan slugging it out in Dundee, helping ensure that the first and therefore third slots go to men. If the left was organised I would say that it certainly benefits them, but from what can be seen from the shortlisted candidates that organisation is lacking.

And who are likely to be the biggest losers? The vast majority of members whose votes will go utterly wasted, and whose lead candidates will have been selected by a system that better resembles a lottery than democracy.